Shirley Jackson wrote her dark, renowned short story “The Lottery” while living on Prospect Street in North Bennington, Vermont.

On a bright spring morning in 1948, she walked down the Prospect hill with a baby stroller for a round of village errands. An hour or so later, Shirley Jackson pushed the stroller up the hill with newspapers, the mail, groceries — and a story in mind. Once home, she set her toddler in the playpen and wrote “The Lottery.” It was published in The New Yorker three weeks later (June 28, 1948).

The story created an immediate uproar. “The Lottery” describes a communal rite in a tidy Yankee village quite like the author’s own. As generations of readers were shocked to learn, community order in the fictional village is nourished by solstice blood. The New Yorker‘s inbox was filled with complaints and subscription cancellations. Shirley Jackson became a national sensation.

In response to questions about the “meaning” of the story, she wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle (July 22, 1948):

Explaining just what I had hoped the story to say is very difficult. I suppose, I hoped, by setting a particularly brutal ancient rite in the present and in my own village to shock the story’s readers with a graphic dramatization of the pointless violence and general inhumanity in their own lives.

In later describing how she came to write the story, Shirley said: “Perhaps the effort of that last fifty yards up the hill put an edge on the story. It was a warm morning, and the hill was steep.”

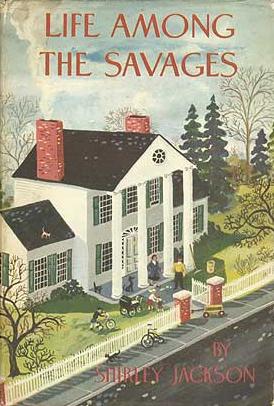

The relationship of Shirley Jackson and her family to the village was uneasily nuanced. She wrote the script for a neighborhood production at North Bennington High School, and her fictionalized memoir of family life in the village, Life Among the Savages (1952), remains a well-loved classic.

Yet her biographer, Judy Oppenheimer, describes a strained relationship between Shirley Jackson and the villagers of North Bennington. She writes that Shirley’s children recall a drumbeat of anti-semitic comments directed at their father, Stanley Edgar Hyman. Ralph Ellison, a regular visitor to the Hyman household in the 1950s, described tense moments of interaction for a Black man in a wholly white village. The Hymans engaged in the rituals of Little League yet endured swastikas soaped on their windows.

Shirley Jackson’s biographer concludes that despite the difficulties, Shirley most appreciated the villagers’ respect for individual privacy. The biography quotes Shirley’s son, Barry Hyman:

You meet [people] in town… You don’t ask questions about what goes on in their land, their house, their clan. That’s sort of why she wanted to live there. She figured she could be anonymous and just write and be happy and sit out in the sun with the dogs and the cats.

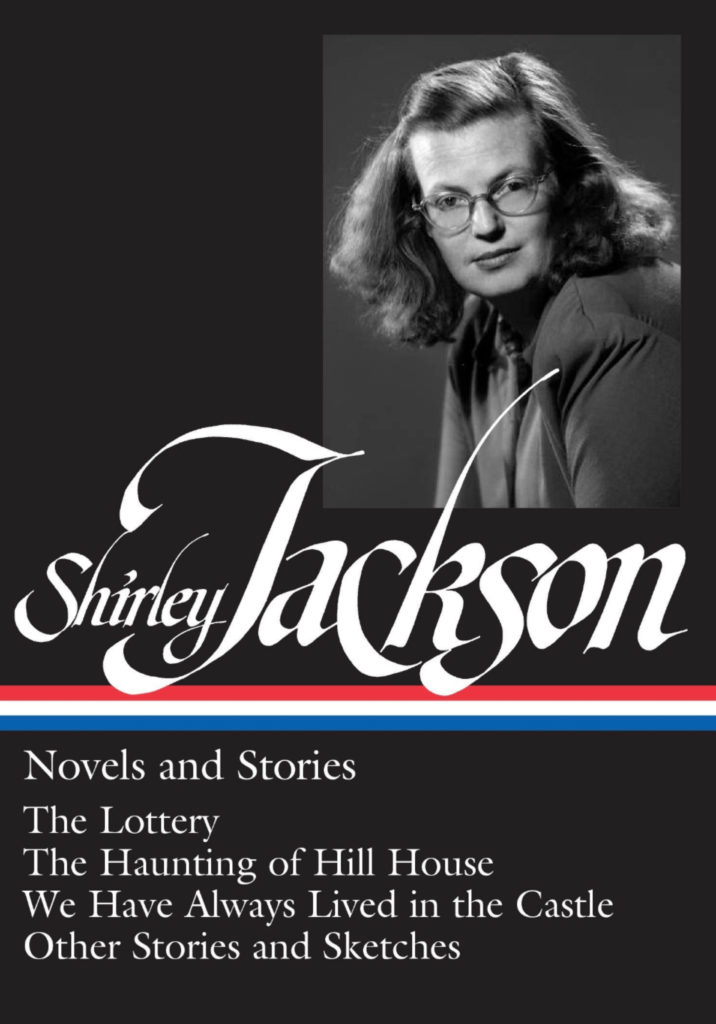

There is currently a revival of interest in Shirley Jackson’s work. The Haunting of Hill House has been reimagined in a Netflix series. A long lost short story – “Paranoia” – was published in The New Yorker on July 29, 2013. Critic Ruth Franklin published an acclaimed biography in 2016. All Shirley Jackson’s work is back in print.

Sources: Oppenheimer, Judy. Private Demons. The Life of Shirley Jackson (1988); Franklin, Ruth, A Rather Haunted Life (2016); interview with Judy Oppenheimer formerly posted in wiredforbooks.org; Wikipedia, “The Lottery” here.

Outside links about Shirley Jackson

A short video about Shirley Jackson’s “haunts in North Bennington.”

A New Yorker article about readers’ responses to publication of “The Lottery.”

Joyce Carol Oates on Shirley Jackson.

Steven King, David Sedaris and other writers talk about how “The Lottery” got under their skin.

Shirley Jackson’s son, Laurence Hyman, on the resurgence in interest in his mother’s work.

Shirley Jackson’s obituary in The New York Times.

“The case for Shirley Jackson”, the New York Times’ 2016 review of Ruth Franklin’s biography.

Ruth Franklin on the ambiguity of “The Lottery”